UHF RFID Antennas - VI - Quadrifilar antenna (Part I)

Hey there folks! Today I’m heading back to the RFID reader antennas topic. This time, I’m covering another typical antenna found in these readers, which is the quadrifilar antenna. In this particular case, a printed implementation of the quadrifilar antenna.

These antennas are composed of four arms, either monopoles or PIFA type elements, where each of the elements is fed with a 90º phase delay in between in order to create a circularly polarized radiation. Another common place for quadrifilar antennas is the helix type antennas used for VHF and UHF band communications and GNSS applications. These are very popular among HAMs and also some commercial applications. Here’s some examples:

|

|

|---|---|

| Quadrifilar helix antenna | Quadrifilar PIF-Antenna |

The main feature of this implementation (Quadrifilar PIFA) is the polarization purity, wide bandwidth (due to impedance stability with frequency of the elements of the antennas, when placed above a ground plane), associated with a rather compact package. Yes, there are smaller antennas, but you trade performance for size and the quadrifilar usually gives a good compromise.

To build the quadrifilar PIFA there’s essentially two major sections that are desgined separately and then combined in the end: The antenna element (the PIFA); and the feeding network. The former being the easiest and essentially based on regular PIFAs with some meandering of the arms in order to reduce the size, while the later is usually the more complex subject, and fitting the complete network within a limited space poses the hardest challenge.

For this post, I based essentially on two papers, this one from Qiang Liu and this one from Xuefeng Zhao. There’s quite a few references available if you search online. I went through a few (and by a few I mean like three or four, I’m kinda lazy), these two were more fundamental and I liked these two the best.

In this post I’ll go through the process of designing such an antenna and focus essentially on the antenna structure and radiation results. On the next post I’ll focus on some alternatives for the feeding network to make it more compact. I took the antenna structure from the Qiang Liu’s paper but mashed it with the feeding network from the Xuefeng Zhao’s paper. It’s the simplest antenna form with the simplest feeding network. On the next post I’ll explore the feeding network shown in Qiang Liu’s paper, which is more elaborate, and also another alternative to have a compact solution. As for the Xuefeng Zhao antena configuration, it is essentially the same IFA antenna approach, but reduces the overall size by bending the monopole arms and by placing the shorting stub of the IFA in the vertical connection between the boards (similar to the antenna on the picture above from the QUBE antenna). So, if I mashed up the other way around, I’d achieve the most compact solution, which I hope I can shown on my following post.

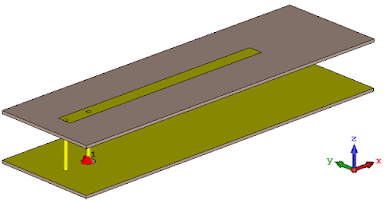

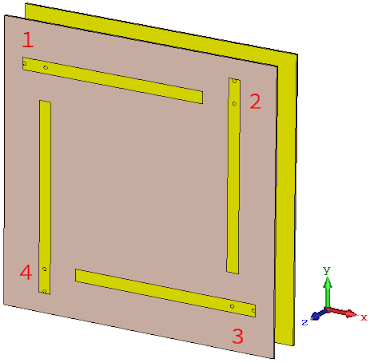

I’ll start with designing the IFA: IFAs are pretty old antennas, no busy covering the particularities of it. But if you’re interested, you can check this page, has a lot of useful resources. It’s easy, you just design an arm on a PCB, place it at some distance from a ground plane (on the picture below, the antenna arm is in the top PCB while the ground is in the bottom PCB), feed it at a given distance from one of the arms edges and place a short circuit pin at that end. Like this:

NOTE: gray zones are dielectric (FR4), yellow zones are copper.

|

|

|---|---|

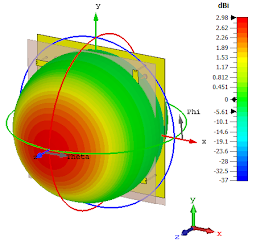

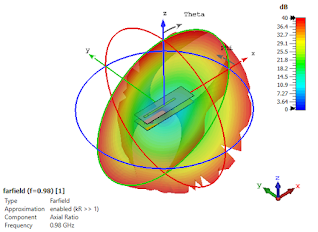

| Radiation pattern (Directivity) at 900 MHz | Radiation pattern (Axial Ratio) at 900 MHz |

|

|

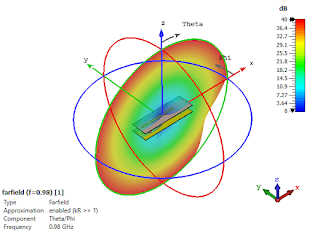

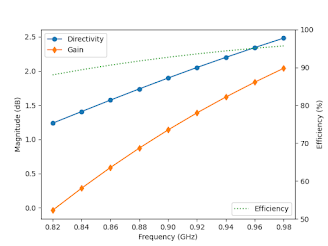

| Radiation pattern (Theta/Phi relation) at 900 MHz | Directivity, Gain and Efficiency with frequency |

As you can see from this results, the main direction of radiation is essentially towards the upper hemisphere, and is quite broad in the YZ axis, which is also referred as the H-plane. This is expected since the antenna would otherwise be omnidirectional in the H-plane, but the ground plane in the bottom makes the radiation reflect towards the upper direction.

The polarization is also linear, since the AR (axial ratio) in the principal radiation direction is 40 dB, and is inline with the direction of the arm, as can be seen from the Theta/Phi relation plot. The gain is also increasing with frequency, which is also expected since the antenna is electrically larger and larger as the frequency increases. So everything looks good, we can move on.

You might be wondering why I’m not showing any S-parameters. Well, because, at this point I don’t care. I’ll have to multiply this antenna by four and design a matching network to feed all the elements simultaneously. The combined effect of the four loads, plus the matching network, being composed of multiple power-splitters, will make the operation bandwidth of the antenna rather large, regardless of the impedance response of each of the elements standalone.

Ok, so we have our base antenna, now we just replicate three times the same design, rotate each element by 90º in relation to the previous and give some slight separation between the elements, so that the distance between each of the arms and the center of the antennas is roughly a quarter of the wavelength, ending up with the antenna as proposed in Qiang Liu’s paper, like so:

Now, in order to obtain a circular polarization radiation, you just feed each of the elements, with the same power amplitude and a 90º phase difference between them. To avoid designing the feeding network to have to check for the array, in CST you can just add a port to each element and then setup the simultaneous excitation in the ‘Excitation settings’ menu, within the ‘Simulation setup’ panel.

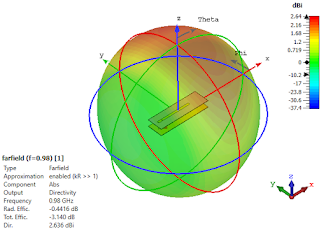

With this setting the radiation results for the 4-element array antenna are the following:

|

|

|---|---|

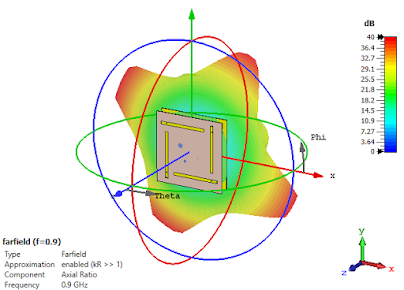

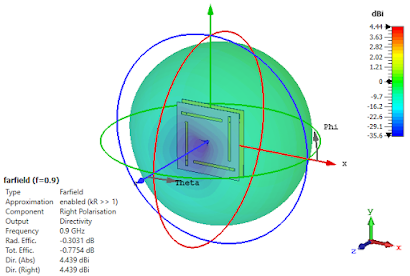

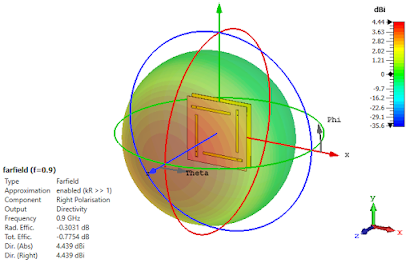

| Radiation pattern (Directivity) at 900 MHz | Radiation pattern (Axial Ratio) at 900 MHz |

|

|

| Radiation pattern (LHCP) at 900 MHz | Radiation pattern (RHCP) at 900 MHz |

As you can see from the results above, the overall directivity of the antenna increased. Which is normal since we have four antennas contributing to radiation. The axial ratio shows that polarization is nearly perfectly circular (this is an ideal simulation since we excited all the ports with perfect 90º shifts, won’t happen in final models I’ll show next post), and also that the rotation set between the ports is correct, the obtained rotations is clockwise (RHCP) as seen from the LHCP and RHCP responses in two bottom pictures.

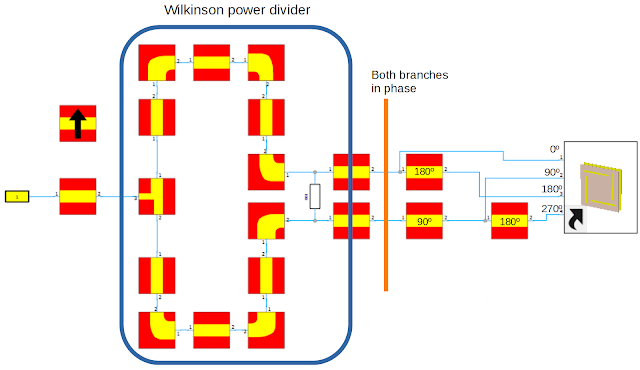

For the matching network I picked up the design from the Xuefeng Zhao’s paper, which is a Wilkinson power divider, with one output delayed by 90º, then followed by delay lines of 180º in each branch, as in the following construction:

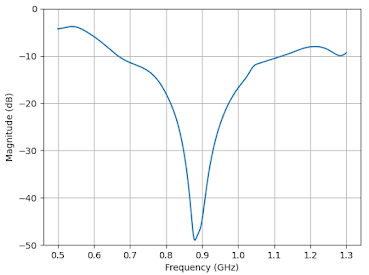

Combining this matching network with the antenna results we can finally have a glimpse at the expected impedance operating frequency, given by the S parameters at the single port input at the entrance of the Wilkinson power divider. Here it is:

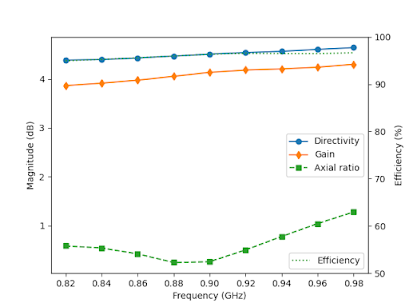

To actually find the whole covered band, we have to look from 500 to 1300 MHz, to discover the impedance bandwidth of this antenna is between 700 and 1100 MHz. Plus, the radiation results for the combination of the matching network with the antenna elements are also very good. The axial ratio is below 3 dB (circularly polarized) through 820 to 980 MHz (more than necessary) as well as the efficiencies ranging above 95% for the whole spectrum. Here’s the plot:

However, the truth is that these results are based on a simulation of ideal transmission lines with a perfect transition to the feeding points of the antenna. This efficiency results are only from the antenna radiation and don’t take into account the loss effect of the feeding network. For that, the feeding network 3D EM model should be simulated and integrated with the antenna. Nevertheless, these results give a pretty good indication that we’re in the right track, and prove all the advantage points I referred at the beginning of this post. The two downsides of this antenna topology versus the air core microstrip patch I’ve shown in previous posts, are the lower gain and the more complex implementation.

The smaller gain is a direct consequence of the reduced size of the antenna. We’re trading size for gain, that’s an essential rule in antenna design, you always sacrifice on gain to achieve smaller package antennas, with some exceptions for more complex techniques with metamaterials and such…

…but that’s a story for another time!

Next post I’ll continue this quadrifilar antenna exploration, but I’ll focus on the feeding networks, exploring two possibilities to make the feeding network smaller. You see, the antenna in this post with the straight monopoles has a package of 90 x 90 mm, an improvement from the patch, but not incredible. The goal is to get to a package of 60 x 60 mm as the QUBE antenna shown in the biggining (or even maybe 50 x 50 mm).

Till then, stay tuned!